“Heroic is a bit strong,” he says, “but I am enjoying it.”

My father has, in recent months, embarked on a writing project. Inspired in equal parts by a) the realization that he won’t live forever, b) encouragement from his wife (my saintly stepmom), and c) the work Tom and I do as life writing coaches -- he has decided to write down some of his life stories.

My father and I have certainly had our disagreements and at first glance are on opposite ends of several lifestyle spectra. But we share a strong love and respect for our heritage and for the old-fashioned “family values” (the real ones, not those perverted by politicians) like respect, caring for one’s neighbor, civility, thrift, honesty, and meaningful work. He was the first to attempt to teach me how to be a decent person, as his very decent parents had taught him. (I hope I’ve learned well enough to not embarrass him.)

I am thrilled to tears (literally) that he is undertaking this project. (And not just because by doing it he’s validated my current career choice!)

My dad, a professional documentary filmmaker and writer, has always been brilliant with words. He recalls writing, as a young man, page after page of prose at lightning speed. “And then I got drafted,” he said. And got married, and had a family, and provided for said family. There wasn’t much time for personal writing. Until now, at age 79. (There still isn’t time, between the films he still wants to finish and the gardening and the traveling.) But he’s making time for it anyway. Why the rush, Dad?

Because he’s running out of words.

The Word Thief -- Broca's Aphasia

Here’s the heroic part:

Recently, my father, the crack wordsmith and loquacious conversationalist, has been diagnosed with Broca’s aphasia. Broca’s is a speech disorder (caused by injury to or deterioration in the limbic system of the brain) defined as “loss of the ability to produce spoken and written language.”

His comprehension and memory and sense of humor are perfectly intact; his problem is with expression. You know that feeling when a word is on the “tip of your tongue” but you just can’t find it? It’s like that, times 100. Torture for a man who has lived his whole life for words.

"In short, it interferes with retrieving words from your brain on demand," he writes in the preface to his memoir. "Suddenly, in the middle of speaking, I’ll blank on a word and the conversation will freeze while I struggle to find it. The funny thing is that it’s still in my memory. I know what the word is, what it means. In most cases I can come up with the letter it starts with, and the number of syllables it contains. I try to bypass it with synonyms or play a kind of charade until the listener gets it... . I become anxious, the thread of attention is snipped, and the listener slyly turns to another interest."

It’s hard for my dad to see a fellow conversationalist’s attention drift as the person waits for what feels to Dad an interminable amount of time to remember the right word. He hates to feel that he is boring someone.

I asked him if the words came any easier in writing than in speaking. Not really, he replied; "words can also refuse to display themselves on paper." But there is less social anxiety in writing. In writing, he can take his time. He can leave out a word, come back to it later and see if it shows up, without the pressure of a real-time listener.

But he’s still in a race against time (if he’ll excuse the cliché) to get these stories down before all the words leave him. Here’s what blows me away: as frustrating as this exercise must be for him, he is determined to keep writing. (In fact, he sounded downright cheerful about it.) He has found some workarounds, ways to trick his brain and use tools to fill in the gaps. It’s slow going, but he persists. That’s what makes this effort, to me, heroic. (Because I know how hard it is to find the right words with a brain only slightly impaired by perimenopause, never mind an aphasiac one.)

Coping Strategies

He has developed ingenious ways of capturing ideas as they come to him, even as the words are elusive. He described seeing memories unroll like a strip of silent film: he can perfectly envision the places and events of his life, some hilarious, others disturbing. (He wants to include them all.) He visualizes the stories, and if he can jot down one word or concept that comes to him in relation to the pictures in his head, it will be enough to remind him at a later time and he can revisit the “film strip.”

"Surprisingly," he says, "a film has a certain immunity to aphasia. It’s force is inherently visual, a flow of images that can evoke emotions and meaning. I habitually see the storyline in my mind first, then lay out a skeleton narrative. If it seems appropriate, the last process is a re-edit to find specific wording that’s compatible with the film’s visual rhythm."

When writing the story, if he gets stuck on a word, he can write a substitute word or leave a blank space and come back to it. Often, in rereading it later, the correct word will suddenly come to him.

He also keeps a thesaurus close by. If he can mentally chase down a similar word, even if it’s not the elusive desired word, he scans related concepts in the thesaurus until the actual word he was looking for jumps out at him.

Words of Hope

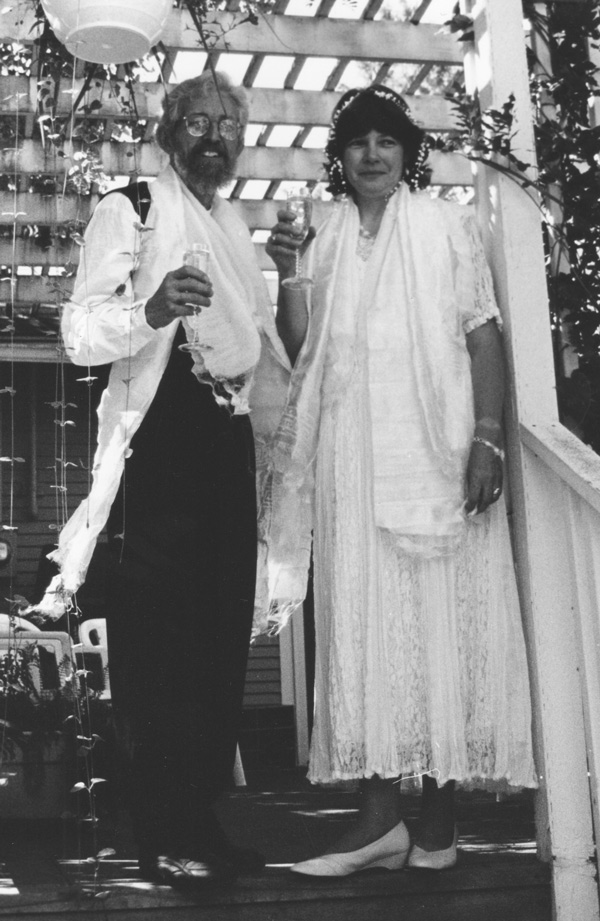

My Dad and stepmom, Cec, at their wedding.

Dad has had an interesting, somewhat unconventional life, a life worth writing about. He still has time, even if his efforts are slowed by having to doggedly chase down the elusive spirits of language.

"Broca’s aphasia has made the task become slower and more tedious, but not impossible," he says. "So, out with the dictionary and the thesaurus, with the hope I can finish before aphasia might mutate into Alzheimer’s."

Keep it up, Dad, because your effort is an inestimable gift to me. And I can’t wait to read it. I will appreciate every hard-won word.