This week we were asked to write a guest post for the Association of Personal Historians blog on the final item in the New York Public Library’s recent post “20 Reasons Why You Should Write Your Family History.” Reason # 20 reads: “You will be encouraged to archive and preserve the documents on which your family history research is based: certificates, letters, diaries, etc.” Here is the post or you can read it on the APH blog here.

Use Them or Lose Them

There is more to preserving your family’s history than tossing it into a cardboard box and handing it down to the next generation. Without context and “curation” —the careful gathering, sifting, selection, and preservation that takes place in any worthwhile collection—your family’s history can be lost to confusion or apathy as easily as it can succumb to dust or mold.

A letter signed by Abraham Lincoln, as anyone who has watched “Antiques Roadshow” knows, can be worth thousands of dollars. But such a document’s worth to us as a nation is far greater. Some of your family’s documents—letters, photos, diaries, ephemera—can be as valuable to your family’s history as Abe’s letter is to America. But do we treat our own with the same care and respect?

As personal historians, we see many clients who are keenly aware of the importance of this legacy, yet who are overwhelmed and weighed down by the responsibility of caring for mounds of family history “stuff.” Having a method of curating your own historical collection is important not just for your posterity, but for your sanity!

Steps for Curating Your Family History Assets

(These steps are expanded upon in our free ebook pamphlet, How to Save Your Stuff: Curating Your Family History Assets, which you can download here.)

How to curate your own family history collection.

A curator of a museum or art collection follows a prescribed set of steps to care for a collection: gathering material, sifting through (determining what is of value) and categorizing, preserving, and selecting for presentation.

We can follow these same steps when curating our own collection of family history documents:

1. Gather and inventory your assets. Take a rough inventory of everything you have. Walk around your home and jot down a quick list of everything that might contain important assets. “Travel slides, garage shelf,” “box of Grandma’s stuff, hall closet,” “Sarah’s school papers, basement” is sufficient detail at this point.

2. Loosely categorize and sort into piles. Devise some loose categories for your assets such as by decade or life milestones such as “childhood,” “college,” etc. (You can also divide by family member or family if you are sorting generational stuff.) These divisions only have to make sense to you, and don’t make your divisions too small or complicated. While in this first pass, throw anything away that is obvious garbage. If you can’t decide, keep it for now.

3. Attack one pile at a time. This can be done over time; setting a goal to tackle one pile a day or week will keep you moving. (For a list of questions that will help you determine whether or not to keep the item, refer to our How to Save Your Stuff free ebook.) You may also find these blog posts helpful:

Minimalism and Family History, Part One

Minimalism and Family History, Part Two

Once you have determined which originals you will keep and pass down, make sure they are stored properly in archival, acid free containers. Store your originals away from heat, light, moisture, and chemicals and make sure you keep a record where to find them!

4. Assess, refine, and label. Once you have gone through a first pass on each pile, look more closely to identify, store, and label or caption each piece. Captions and labels are crucial for identifying each asset for others who will use this archive.

5. Digitize. Properly scan your photos and documents, and have film digitized by a reputable vendor. Photograph memorabilia that is not scannable.

Digitized assets can be organized, stored, and shared in an archive book/media combo.

6. Create a digital and physical archive. Consider the best methods for backing up your data on archival disks or other storage media. Store in the cloud or share online as well as on physical media. Make and share multiple copies of your archive; redundancy is the key to safety of digital assets!

7. Display highlights of your collection in a form that can easily be enjoyed and shared, whether online or in a family history book, or both! Books have an advantage in that they will never become obsolete and need no device or power to view.

Once you have decided what to keep, display the most special finds in a family history book.

What assets (documents, etc.) should I consider?

- Correspondence. Letters, postcards, telegrams, notes, family newsletters.

- School and career documents: Certificates, speeches, articles, newspaper clippings, military documents, professional papers, report cards, ID cards

- Personal writings: journals, diaries, written or typed histories, memoirs,

- Photos: Prints, slides, negatives, scrapbooks, photo albums.

- Multimedia: Films, videos, audio recordings, social media content.

- Memorabilia: Objects with sentimental or historical value, such as jewelry, antiques, furniture, toys, artwork. Photograph important objects, even if you decide to keep them.

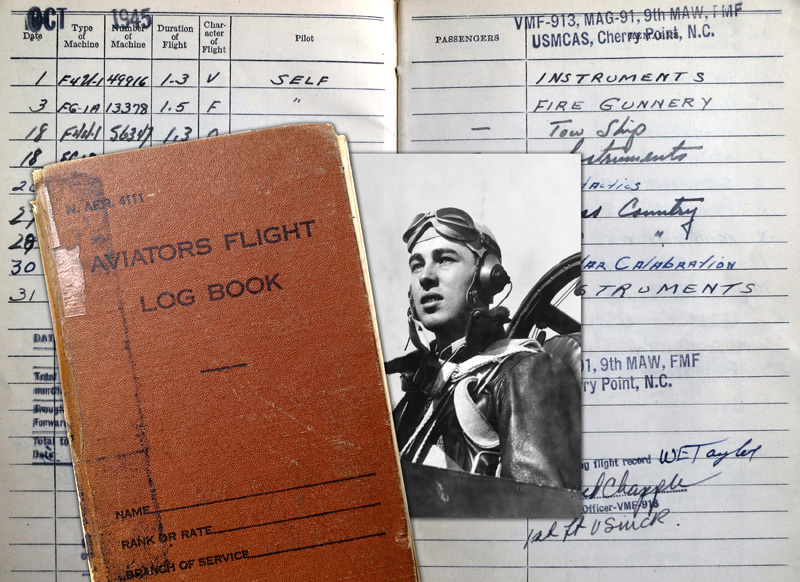

- Ephemera: Even items that seem to have little historical significance can provide insight into lifestyle and add charm and visual interest to your life stories. Travel documents, concert tickets, receipts, calendars/planners, log books, sheet music. (One of our clients wrote a note to his wife on her brown paper lunchbag each morning; she tore off the notes and kept them all!)

Unusual paper items can add interest to a family story.

In looking over this list, don’t forget to back up and preserve your digital assets (emails, blogs, photos, videos, and social media content.) Digital assets are vulnerable to loss and damage just as much as paper, if not more so!

How will you save your stuff?

For more articles on the topic of personal and family history, visit our blog at Pictures and Stories or get our book How to Save Your Life, One Chapter at a Time.